Notable Changes in the new FDA Draft Guidance – Content of Premarket Submissions for Device Software Functions

The FDA released its new draft guidance for the Content of Premarket Submissions for Device Software Functions on November 4, 2021. Once approved, this guidance will replace the preexisting Guidance for the Content of Premarket Submissions for Software Contained in Medical Devices released in May 2005. A lot has changed in the last sixteen years where medical devices and software is concerned; the FDA released the new guidance citing technological advancements in all facets of health care, which has caused software to become an important part of many products and medical devices. The most impactful changes that we should be aware of from the guidance are as follows:

- Change from Software Level of Concern (Major, Moderate, Minor) to Documentation Level of Concern (Basic, Enhanced)

- Expanded scope, including –

- Introduction of the term software function

- Introduction of Software as a Medical Device (SaMD)

- Addition of DeNovo Classification Request and Biologics License Application (BLA) to the premarket submissions to which the guidance applies

- Introduction of additional consensus standards and guidance documents, including –

- ANSI/AAMI/IEC 62304: Medical Device Software – Software Life Cycle Processes

- Off-The-Shelf Software Use in Medical Devices

- Provision of Examples (Documentation Level, System and Software Architecture Diagram Chart Examples)

RELATED: Understanding FDA Medical Device Class and Classifications, and its Impact on Requirements Management

Let’s analyze each of these changes and determine how impactful the change will be.

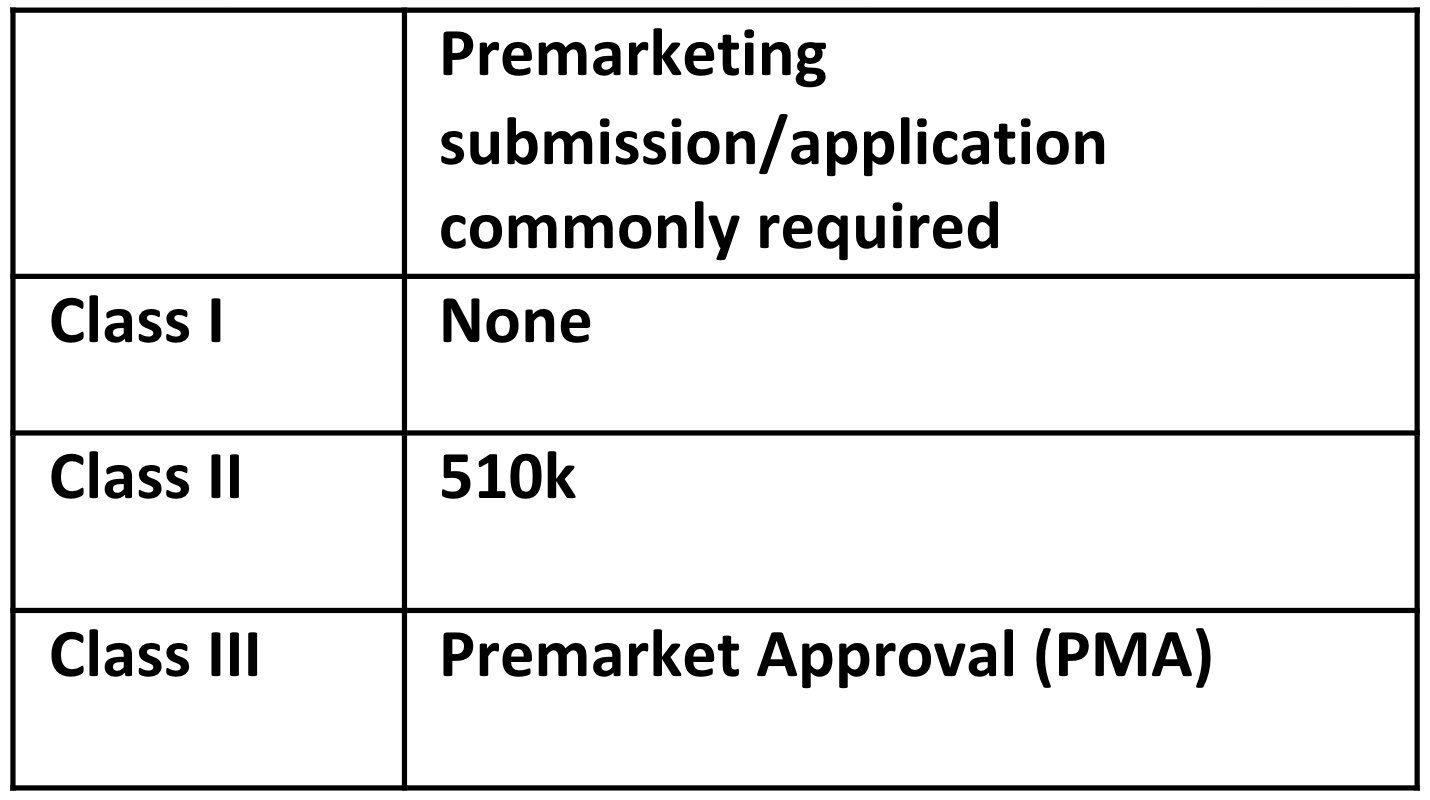

Where the change from Software Level of Concern to Documentation Level is concerned, there are several important things to consider when analyzing, the foremost being that Software Level of Concern is no longer used. The FDA now describes it as Documentation Level, which is more germane to the information conveyed. Additionally, the Documentation Level name change also avoids confusion with the IEC 62304 Software Classification and has the benefit of simplifying the process for determining the documentation level. Limiting the documentation level to two levels streamlines the process, as the only differences between the Moderate and Major Software Levels of Concern were the requirement to provide a Configuration Management Plan and Maintenance Plans instead of summaries, and the addition of Unit Test and Integration Protocols for the Major level of concern. Other changes related to the documentation to be provided are generally quite subtle, such as requiring the Risk Management File rather than just Device Hazard Analysis as specified by the current version of the guidance, and what used to be Software Development Environment Description being redesignated Software Development and Maintenance Practice. These changes create a tighter alignment with IEC 62304, highlight the importance of risk management and simplify the use of the guidance.

Although the scope of what the guidance is intended to cover remained unchanged, there are three new terms discussed in the scope section which serve to emphasize areas of importance to the FDA – device software function, Software in a Medical Device (SiMD) and Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). The term device software function is used to highlight the fact that a product could have multiple functions, a function being a distinct purpose of the product. SiMD and SaMD are new terms used in the industry, although the types of software covered by each term were already present in the original version of the standard. The premarket submissions for which the guidance applies now included the De Novo Classification Request (on July 9, 2012, FDA allowed a sponsor to submit a De Novo classification request to the FDA without first being required to submit a 510(k)) and Biologics License Application (as of March 23rd, 2020, all biological products must be approved through the BLA pathway), both of which were introduced after the current version of the guidance document. These changes serve to modernize the terminology used in the guidance and highlight the importance of the guidance being applicable to SaMD.

Another important update in the guidance is the mention of IEC 62304. This standard was first issued after the original FDA Guidance was released in May 2005; in the draft guidance, the FDA explains the relationship between its own draft guidance and IEC 62304. IEC 62304 is a software lifecycle process, whereas the scope of the FDA draft guidance is only the facilitation of appropriate review of premarket submissions, allowing for the evaluation of safety and effectiveness of medical devices. Since IEC 62304 is an FDA-recognized consensus standard, the FDA is allowing a Declaration of Conformity to IEC 62304 as documentation for Software Development and Maintenance Practices required by the draft guidance. In addition to the use of IEC 62304, the draft guidance also references other FDA guidance documents related to Cybersecurity and off-the-shelf software, which were likewise not available when the original version of the guidance was published in 2005. These changes also help modernize the guidance and demonstrate the importance of IEC 62304, as well as providing an indication of key areas that the FDA will expect to be addressed in future 510(k) submissions.

RELATED: Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Four Key Development Best Practices

A further significant addition to the draft guidance is the inclusion of examples related to Documentation Level and System and Software Architecture. The examples included in the guidance provides different scenarios to show how to arrive at the Basic or Enhanced documentation levels. The draft guidance also provides an example of an architectural decomposition that can be applied to a system or software. In showing these diagrams, the FDA is proposing a level of documentation in the architecture document unseen in other FDA software-related guidance documents. The examples include different “functions” and are inclusive of SOUP (Software of Unknown Providence) modules. The inclusion of these examples provides an indication of FDA expectations when it comes to the documentation of software architecture and ensures that the new approach to determine the level of documentation required is well-understood.

In summary, the FDA Draft Guidance has been updated to bring it up to date with current standards and other guidelines that have been released since the initial guidance. There has been some level of simplification by substituting the software level of concern with basic and enhanced levels of documentation. Additionally, the guidance addresses current hot topics such as SaMD and IEC 62304. Examples have been added to the guidance to make it easier for users to understand and implement correctly.

RELATED